Prof. reminisces about working with Nobel Prize winner

When I was leading the Castleton London Semester in 2006, we visited the British Library and I found myself wandering through an exhibit of the past winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature. And there among the famous laureates, T. S Eliot and William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway, was my first real boss after I was discharged from the Army, Toni Morrison.

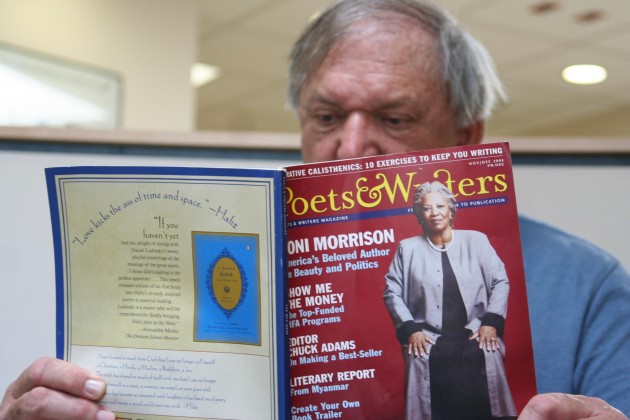

Chloe – no, no one ever called her that except her mother – Toni was the Nobel laureate in 1993, long after I had known her. I knew Toni years before she became a superstar. At that time she was just a single mother, hailing from Loraine, Ohio, an African American who got a B.A. from Howard, an M.A. from Cornell, taught at Texas Southern, and now worked in educational publishing.

I first met Toni in the fall of 1968 when I went for an interview at L. W. Singer publishing company at 501 Madison Ave. in New York City. I could tell I wasn’t what she had had in mind as an assistant. I guessed the obvious, because I wasn’t a black woman (we didn’t say African-American in those days); however, the major stumbling block, as I later found out, was that I had been in the Army. In my defense, there had been a draft during the Vietnam era, and I had silently rebelled by wearing my hair too long and occasionally donning red socks.

“How well do you know the Chicago Manual of Style?” she asked me, after it sounded like I had the position.

“I know what it is,” I replied.

“Know it cover to cover,” she said leaning back, taking it off the shelf behind her, throwing it toward me. For a heavy woman, she was graceful, athletic, though she ridiculed football as a sport where men could legally pat each other on the bum. “Sleep with it, if you have to,” she said.

“Yes, mam,” I said, belying my Missouri background.

“Don’t you mam me, sir,” she intoned in her stentorian voice, a voice that commanded the attention of everyone on the fifth floor.

Almost saying “no sir,” I remained mute.

And thus began my career as Toni’s editorial assistant. The next morning I woke up, the light of the gooseneck desk lamp in my eyes, the orange book resting on my chest like a lover.

The L. W. Singer Company was an educational publisher out of Syracuse, where Toni used to live, but when Random House bought the company, Toni along with Singer, was transplanted to New York City. It was in Syracuse that Toni used to get up early before her two young boys, Ford and Slade, woke up and had to be readied for school. Back in those days, she wrote on an ironing board in the kitchen. That was one reason she and Tilly Olson were such good friends: they both had written on ironing boards.

Before I knew the Chicago Manual of Style cover to cover, the company had moved across town to the Random House building at 201 East 50th Street. It was always a pleasure to tell people I worked at Random House for I could see that special look in their eyes. Later on, it would be that way when I said I had worked for Toni Morrison.

There are some things about Morrison that I still recall. She was hopeless in simple math. I practically balanced her checkbook, something I didn’t even do for myself. Before she figured out her hair and her wardrobe, she didn’t look the part of a rising star in the literary world, but more like someone who might be taking the service elevator. (I do not say this with any disrespect or racial overtones, as I have been asked, because of my less than impressive appearance, to take the service elevator more than once in more than one building on Park Avenue.) She also had a habit of occasionally sucking her teeth, which sometimes made me feel she was unhappy with me. On the other hand, she liked pea soup and cream cheese on date-nut bread from Chock Full ‘O Nuts almost as much as I did.

Slowly, her reputation grew. Over a long weekend she and I put together an introduction for a school dictionary when the professor with the long list of credentials was unable to deliver his own intro. I would say we wrote it, but Toni did the heavy lifting; I thought up some examples and did some typing, but she developed the brunt of the 60-page manuscript.